In the wake of the pandemic, the world economy has been profoundly altered. States around the world have engaged in a dizzying, desperate race to rebuild their economies and stabilize their populations – and we’ve seen a lot of casualties. How did this happen? Who are the victims? And what does this mean for our global economy as a whole? Join us as we explore these questions and more in this post on The Economy after The Pandemic.

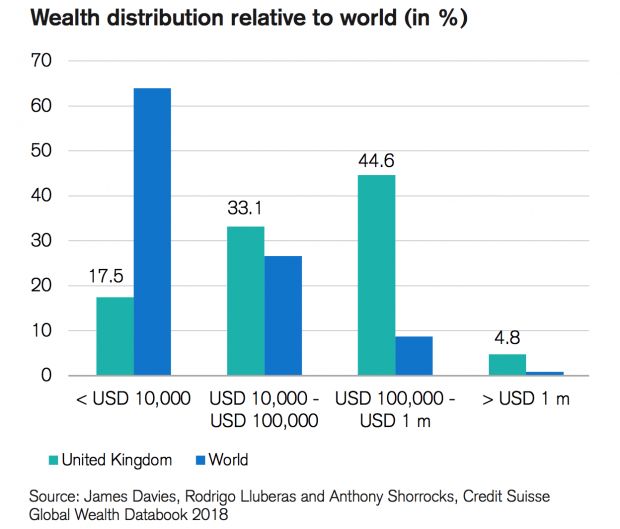

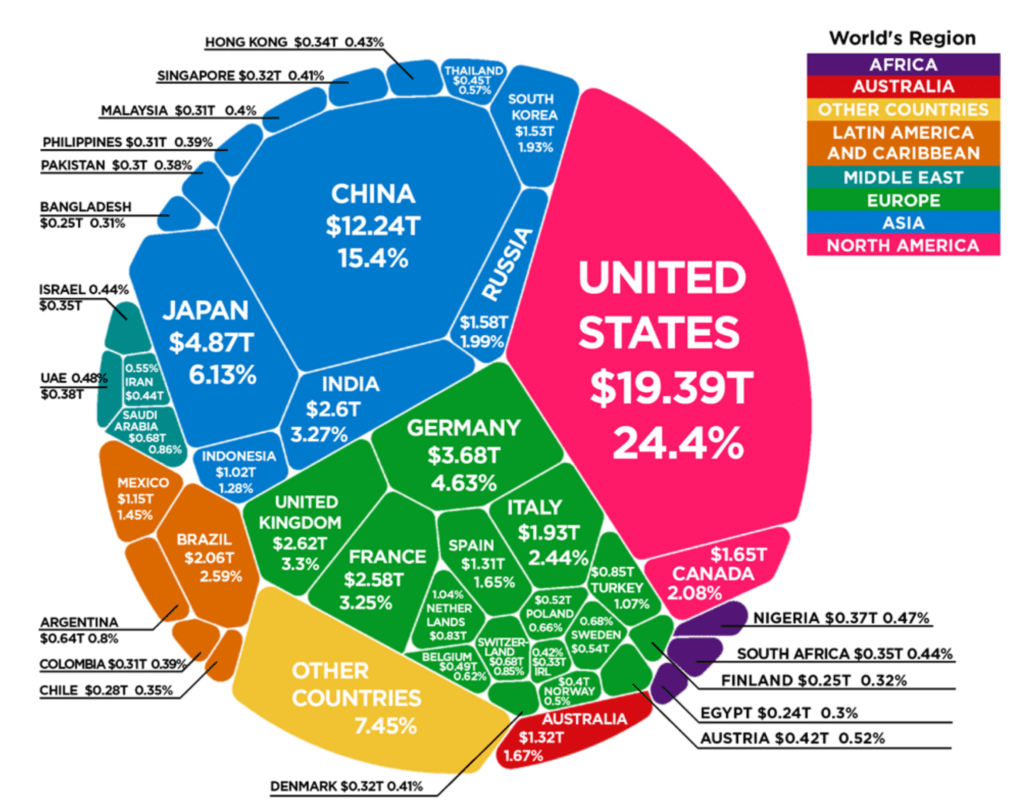

The world was already in a precarious state of economic imbalance before the pandemic struck. Obviously the wealth of nations is not distributed uniformly. The top 10% of earners in the Global North earn about 100 times what the bottom 10% earn, while there is a greater disparity between rich and poor inside the Global South.

This results in an unequal flow of capital that systematically disadvantages poorer countries, which have neither the capacity nor resources to compete with wealthier countries for trade deals, overseas investments, and global markets. They are exploited by these more powerful countries – often through things like sweatshops and child labor – and those vast differences in income mean that when something like the pandemic hits, they are hit harder.

However, it is important to point out that the issues with global capitalism and income inequality are not limited to the Global South. The Global North is also a victim of its own exploitative trade policies. For example, in 2002, George W. Bush’s administration implemented tariffs on steel imports that raised the price of steel domestically and helped drive a nail manufacturing company in Wheeling West Virginia out of business because they couldn’t compete with cheap imports from China and Europe. The company had employed 250 people at its peak and been in business for over 100 years before it shut down. Its employees were forced out of work; many of them ended up on food stamps.

Our current economic system is a tragedy for everyone: the rich, the poor, and the middle class. If we are to survive – if we are to heal – we must change this system. The disease that destroyed our world has laid bare the fault lines in our economies and exposed them for all to see. It is a wake-up call that we must not fail to heed. Now more than ever, we need a radical shift in the relationships between people and their governments, between people and their employers – even between people and each other.

A lot of this is the result of our modern economy favoring corporations over people, but also the result of increasing geographic inequality: economic performance in cities like New York and Chicago have been booming while those in Detroit and Youngstown have utterly collapsed. The rich get richer while everyone else slips further into poverty – this is something that anyone can see even without looking at the data. All of this must be fixed. But how?

How to fix the economy after the pandemic?

Just as the super-rich reaped the benefits of unlimited wealth before the pandemic, so they must take responsibility for fixing their own imbalances. A global wealth tax would be a start, but we need more than that. Ultimately, income inequality is getting worse where it exists, and not better – this is a failed system. It should be replaced with something new: a real economy of people and places – real communities where people support each other rather than exploit one another.

So how do we build that? Well, we could start by examining our cities to see what lessons they have to teach us about what does and doesn’t work in an economy. For example, there are a lot of different ways to run an economy: it is hard to generalize about how cities are run and what works for everyone. However, we can look at the principles that guide their respective economies – the rules and regulations they implement that affect the lives of its people – and try to map them onto our own. The goal would be to identify a set of principles that we could apply across diverse places and technologies, so that there is not just one model of economic success but a range of alternatives from which each city can choose.

This won’t be easy; it is going to take generations to rebuild the system.